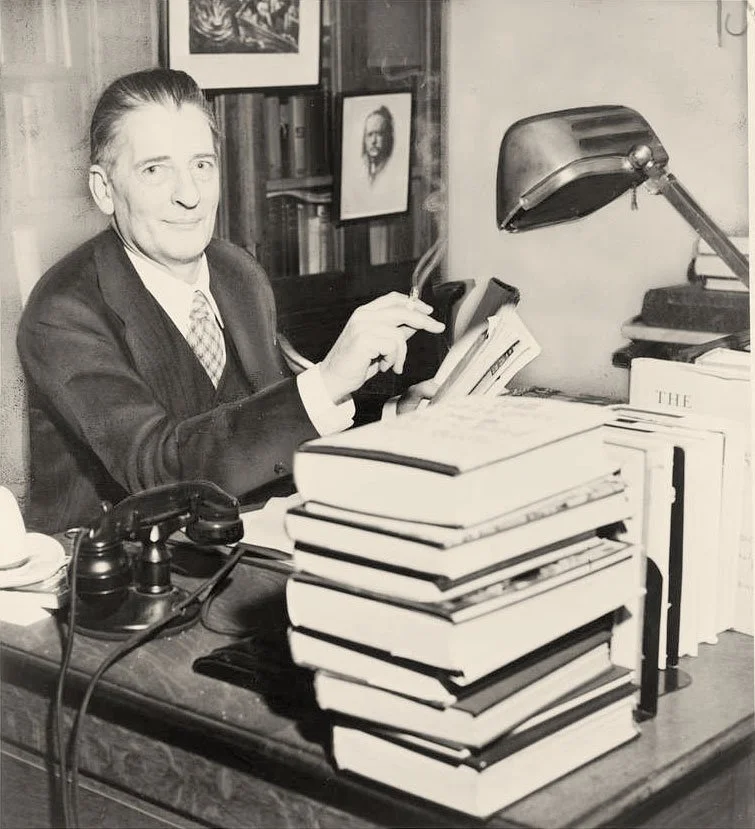

Henry Volkening: The Literary Agent Behind Donald MacKenzie’s Success

Diarmuid Russell and Henry Volkening (standing, sitting at far right) at a Doubleday publication party for Eudora Welty’s A Curtain of Green and Other Stories, November 1941. Russell was Welty’s longtime agent. Others (from left to right): John Woodburn, Welty’s editor; Welty; Ken McCormick, editor at Doubleday; Eugene Armfield, Publisher’s Weekly (where this photo first appeared) and Robert Simon, president of Carnegie Hall. PHOTO CREDIT: Author and Agent by Michael Kreyling, 1991.

Donald MacKenzie’s unrevealed past of criminal activity is compelling, but so are the several years he spent apprenticing as a fiction writer while in prison. In the early 1950s, he was fortunate to find a literary agent who helped channel his pent-up energy, experiences, and creativity into a commercial direction. While this relationship is mentioned briefly in his autobiographical Occupation: Thief (1955), the correspondence he exchanged with Henry Volkening five years earlier offers a far more nuanced look at the fledgling writer’s personality, his musings, and his hopes.

These letters, often several in a week, also give voice to Donald’s frustrations as he struggled to translate his lived reality—criminally evocative and often exotic—into the kind of fiction that magazine editors actually wanted to buy for their readers. In those early days of knocking out short-story manuscripts from his jail cell, Donald was continually bewildered by the distinction between reality and realistic fiction, and many letters between inmate and agent revolved around this dilemma.

“Henry responded promptly to Donald’s letters, usually within a day or two. His neatly typed replies were filled with advice, though never prescriptive or lecturing.”

Diarmuid and Henry at Diarmuid’s home. Despite the smiles here for Eudora’s camera, the two partners didn’t get along and rarely spoke directly to one another. PHOTO CREDIT: From Eudora Welty’s collection, reprinted in Author and Agent by Michael Kreyling, 1991.

To say that Henry Volkening—of the Manhattan literary agency Russell & Volkening co-founded with Diarmuid Russell—was encouraging does scant justice to the word. To Donald, sitting in his cells in Sing Sing Prison and later Auburn State Prison in upstate New York, hammering away at his typewriter, Henry and staff member Connie Cunningham became family. They were his lifeline to a future beyond the prison walls—and he knew it. In these early letters, he bares more of his soul than he would in his autobiographical accounts—perhaps more than he would reveal to anyone during his lifetime—yet even here he holds back, prevaricating in anecdotes about life in England during WWII, his failed marriages, and his precarious postwar hustles.

Henry responded promptly to Donald’s letters, usually within a day or two. His neatly typed replies were filled with advice, though never prescriptive or lecturing. He forwarded Donald’s manuscripts to editors at Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and Atlantic Monthly whenever he felt the stories were ready—and he was equally straightforward when they weren’t. In a letter dated February 9, 1950, Volkening wrote:

I’ll send them out, both COMMAND PERFORMANCE and UNCERTAIN PASSAGE, and I hope we’ll have luck with them. They’re nicely told. If there’s no interest, it will be on one or both of two scores: (1) They are really rather synthetic, and weak on characterization. (2) The surprise ending in UNCERTAIN PASSAGE is, I’m unhappy to say, no surprise to me. Some editors may feel that it might be to their readers. That would improve chances. COMMAND PERFORMANCES, though there I’ll admit the surprise was quite cleverly withheld, strains quite a bit for its artificial effect, with artificial people. The other stories, by the way, are still going around, though I’m afraid they are beginning to approach the end of their respective trails.

Max Perkins (1884-1947) was an editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons, best known for his work in bringing Thomas Wolfe’s novels to publication. He is also remembered for discovering authors F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Alan Paton and Erskine Caldwell. Perkins was the connector who brought Diarmuid Russell and Henry Volkening together. PHOTO CREDIT: Public Domain.

Henry Volkening and Diarmuid Russell opened their agency in 1940 at the urging of legendary editor Max Perkins. According to Harriet Wasserman, a longtime agent at the firm, Perkins advised Russell to start an agency “before the damn women take over the entire business”—a remark Max would no doubt phrase differently today. In her 1997 book Handsome Is, Wasserman describes Russell—the son of Irish writer and nationalist AE Russell—as “very tall and handsome, an outdoorsman type,” while Henry “was the exact opposite… a little indoors guy. Henry wrote long, gushy letters to clients and editors; Diarmuid wrote one-line notes.”

Every manuscript Donald sent to Henry had to include the statement: If this writing is accepted for publication, no mention must be made of the fact that the author is a prisoner in a New York State Prison.

Henry had a master’s degree in literature from Harvard, a law degree from Fordham, but was working in the family’s real estate business in the late 1930s. Henry was one of the only real friends of novelist Thomas Wolfe. They met in 1926 when both were teaching literature at New York University night school and stayed in touch through the 1930s, often in the form of letters and postcards when one or the other was traveling in Europe.

On Wolfe’s death in 1938, Henry reached out to Max for advice on writing an article about his friend. This resulted in “Tom Wolfe: Penance No More”, which was published in the Virginia Quarterly Review. The connection with Max—and a strong desire to get into the literary business—led to Diarmuid and the formation of the firm. Each partner put up $5,000. Together, they built one of the most distinguished client lists in the city: Saul Bellow, Eudora Welty, A.J. Liebling, Bernard Malamud, George Plimpton, Barbara Tuchman, Annie Dillard, and many others. In those early years, the agency was located in midtown Manhattan, in the handsome Fred French Building at 551 Fifth Avenue.

Donald benefited enormously from Henry’s long (gushy, perhaps) letters. By requirement of prison authorities, every manuscript the inmate sent to the agency had to include the statement: If this writing is accepted for publication, no mention must be made of the fact that the author is a prisoner in a New York State Prison.

Constance (Fleming) Cunningham was born in 1910 and went to business college after high school. This photo is probably around the time when she started working for the pulp magazine, Adventure. She joined Russell & Volkening shortly after the agency was opened in 1940. PHOTO CREDIT: Alexandra Sellon from her website, aksellon.com

Connie Cunningham was the first—and for many years the only—employee of Russell & Volkening, according to her niece Alexandra Sellon. Before joining the agency, she had worked as secretary and assistant to Arthur Hoffman, editor of the popular pulp magazine Adventure. Known for the kindness and sincerity of her rejection letters to aspiring writers whose manuscripts never rose above the slush pile, she became Donald’s more personable agency voice, sharing gossip, keeping him apprised of Henry’s whereabouts, and, as the years went on, when the next royalty payment would be wired. He came to depend on her.

Shortly before Donald’s deportation back to England in September 1952—to serve out the balance of his original February 1947 sentence for shop-breaking and receiving stolen property—Connie did him a great favor. He was granted a “day out” from the Federal House of Detention on West 11th Street in New York City to cash a check for $675, his net after the standard 10% agency commission, for a story sold to Collier’s. (That’s roughly $8,250 in 2025 dollars.) Connie met Donald and his armed federal escort at the bank on Fifth Avenue and provided the identification needed for him to cash the check. Despite their long and close “pen-pal” relationship, it was almost certainly the only time they met in person. Donald never believed he would be allowed back into the U.S. after his deportation—and he never tried.